My coaching philosophy.

As a coaching psychologist, my areas of focus are on personal development, stress management, resilience, transitions, and health and well-being.

Learning, skill development, awareness, prevention and optimisation are at the forefront of my coaching, working with people and organisations.

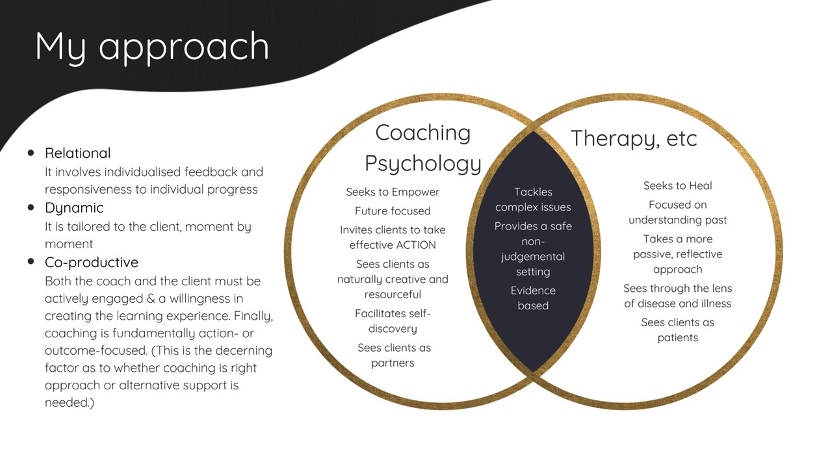

My approach is holistic, combining evidence-based approaches. I draw knowledge from a background of counselling, coaching, organisational psychology and bereavement counselling.

Coaching psychology is focused on enhancing life experiences, work performance and well-being, through the systematic application of models grounded in psychological approaches.

The aspiration of my practice is to facilitate my clients to move ‘beyond zero point’, moving up the positive scale to flourish.

My ethos is to equip my clients with knowledge, tools and strategies, transferring what we do in coaching into all areas of life; leaving them with their own unique tool kit, to thrive.

“Coaching psychology is for enhancing well-being and performance in personal life and work domains underpinned by models of coaching grounded in established adult learning or psychological approaches”

(International Centre for Coaching Psychology [ISCP], 2022).

Figure 1: Illustrates the holistic approach between personal and professional taken in my practice.

Figure 2: Illustrates the pluralistic approach taken in my practice.

In my practice I adopt a pluralistic view. A pluralistic approach to coaching is viewed not as a “set of techniques but a commitment in practice to deeply value the coachee’s needs, which can be achieved by encouraging him or her to actively participate in the management of the coaching process”

(Utry, et al., 2015, p.47).

Additionally, Cooper & McLeod (2011) state that a wide variety of approaches and philosophies are drawn on in pluralistic practice. This is focused on collaborative dialogue between practitioner and client, with clients being keenly encouraged to become involved in decisions regarding which interventions to utilise in the coaching process; with coaches’ negotiating with the clients which techniques or interventions would likely assist them.

The anchor of the process is the coachee’s goal, providing the basis for which discussions regarding tasks are undertaken; for which consideration of and negotiation on which method-specific activities may be considered to complete the task

(Utry, et al., 2015).

The following steps are suggested in a pluralistic coaching practice, which I adopt in my practice.

Provide information about coaching prior to the first meeting, so the coachee will know what to expect in the session. This can be supported by a brochure, telephone call, or email about the approach.

Establish a feedback culture from the beginning by reminders to the coachee that the coach is interested in his or her ideas, preferences and feedback.

Explain the different options that are available to coachees, and what these would actually mean in practice. Provide evidence, where available, on the typical outcomes of particular ways of working.

Engage in metacoaching communication with the coachee about the process of coaching itself. Review goals, methods and tasks on an ongoing basis. This may be particularly helpful if coach or coachee are uncertain about what is happening in the coaching, or if there is a rupture in the coaching relationship.

Actively invite discussion on all aspects of the coaching work, from duration, through payment, to possible involvement in research. This discussion can prove particularly interesting as the digital age offers a range of non-traditional ways for interaction, such as instant messaging or even communicating with pictures.

Adapt the style of relating to the coachee’s needs and preferences. Different people have different needs and this can mean to adapt to at what level a coachee wants to collaborate.

Use outcome forms (for instance, a goal assessment form) to monitor progress in a way that fits the coachee. This can help to keep the process of coaching on track.

Use process measures to facilitate conversation about preferences and the process itself.

(Utry, et al., 2015, pp. 48–49)